“You will see what you want to get”

with Bonolo Kavula

Share

An experimental print-maker with sculptural and textile sensibilities, Bonolo Kavula approaches contemporary art as a restorative practice, both for her as an artist and the viewing audience. Considering her offer of respite, this week’s Re:View examines her recently opened solo exhibition, Lewatle. Nkhensani Mkhari describes their practice as a “queer meditation on transcience, aesthetic sociology and redemptive futurologies.” Primarily curating new media, their instinct is led by the urge to defy demands of technical efficacy and ableism while thriving towards transparency. Featured in this week’s Artist Of Interest, in conjunction with their show Model, we present their thoughts on curatorial care, vulnerability, linguistics and neutrality.

The Indian Ocean covers some 20% of the world’s oceanic surface area. Going from the East African coast to the borders to Northern Asia, it then goes on to surround Australia in the East before bleeding into the Southern Ocean. As a site, it is charged with themes including forced migration, colonialism, segregation and in recent pop culture turn, luxury. As a material it acts as a fluid Afrasian joint, facilitating continental connections. In Lewatle, a solo exhibition by Bonolo Kavula, the ocean acts the primary reference through which the artist studies and stretches the scale, movement and spatial capacities of her work. Open, expansive, engulfing and indefinite, it speaks to Kavula’s abstractions.

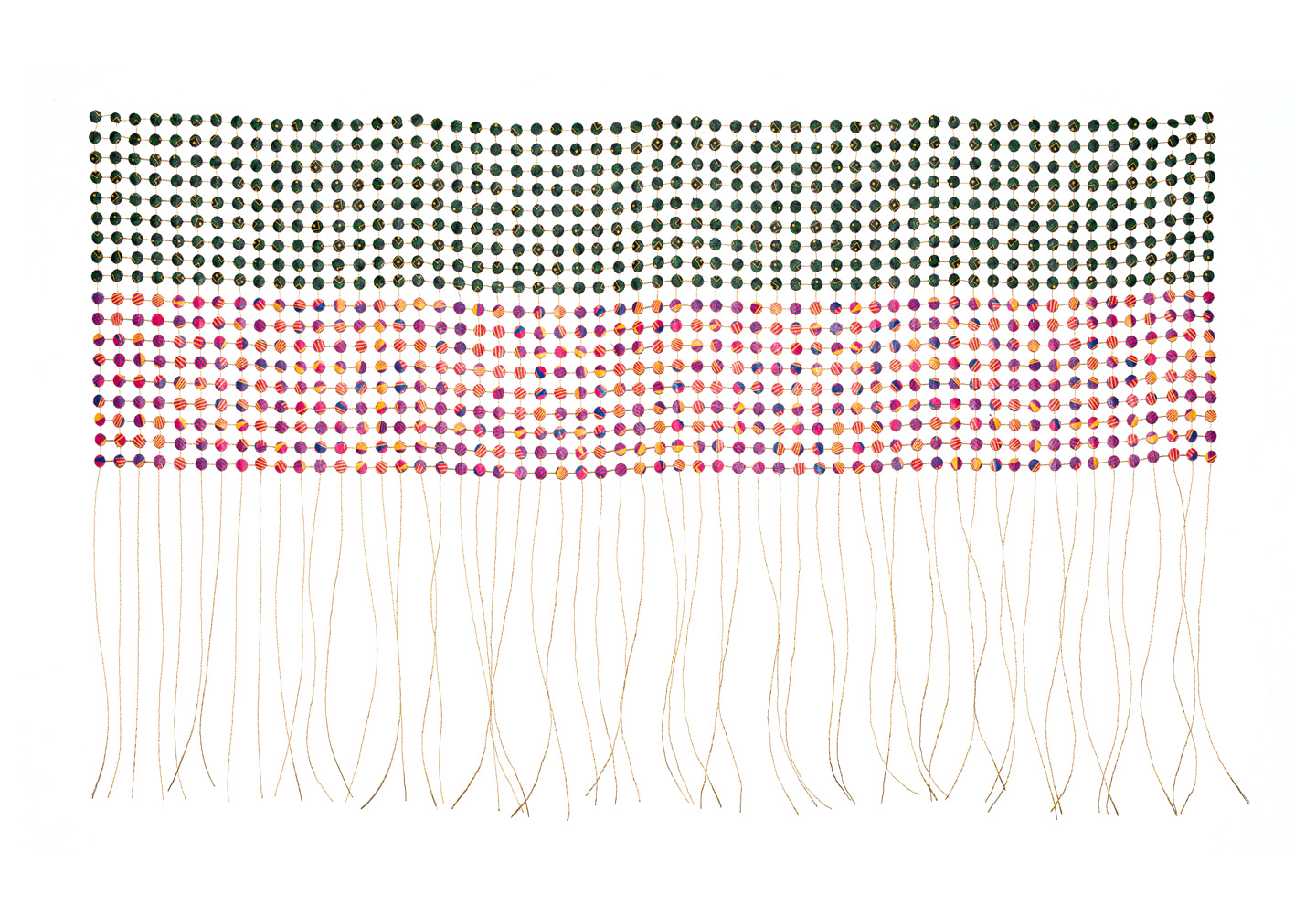

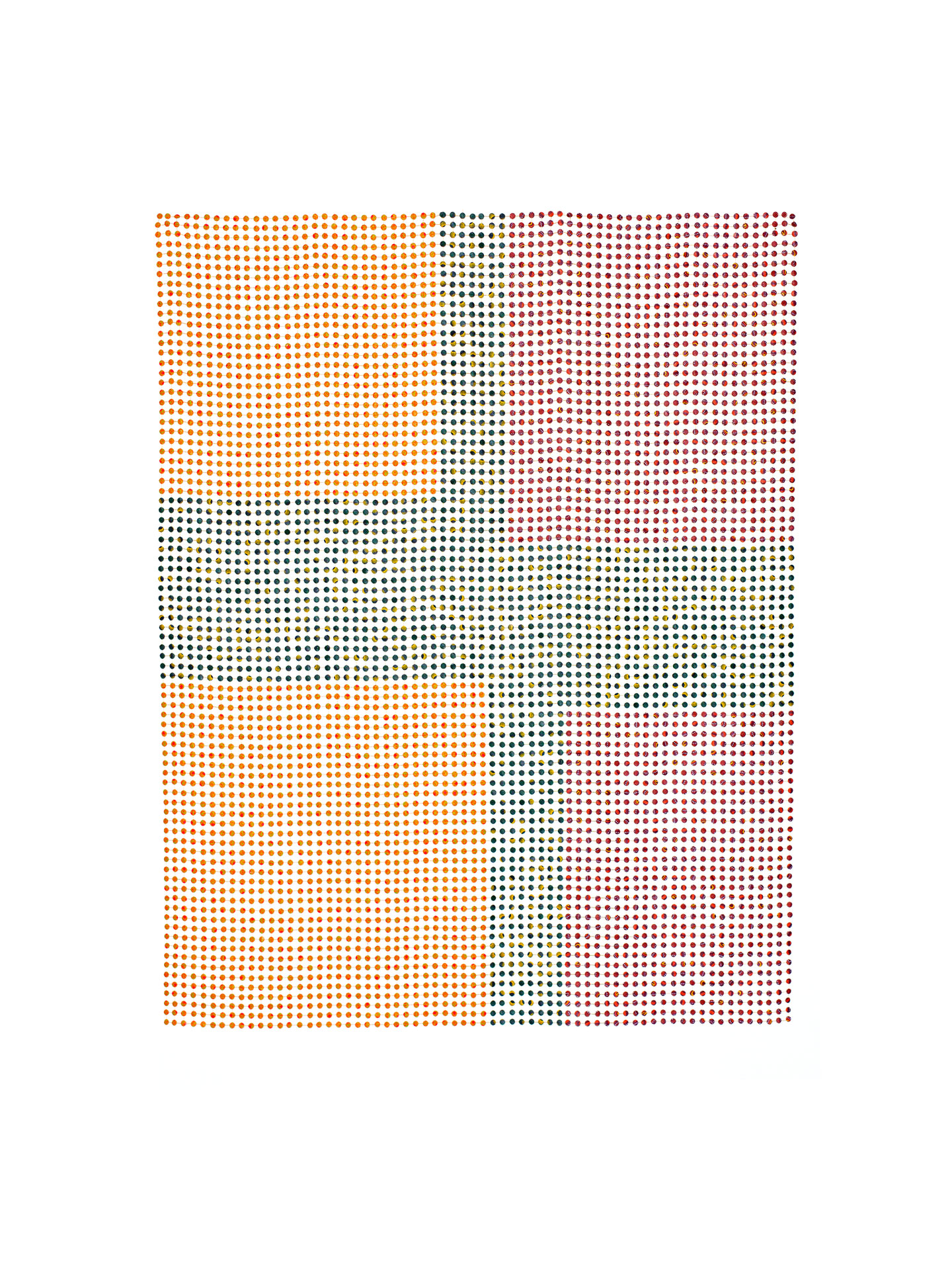

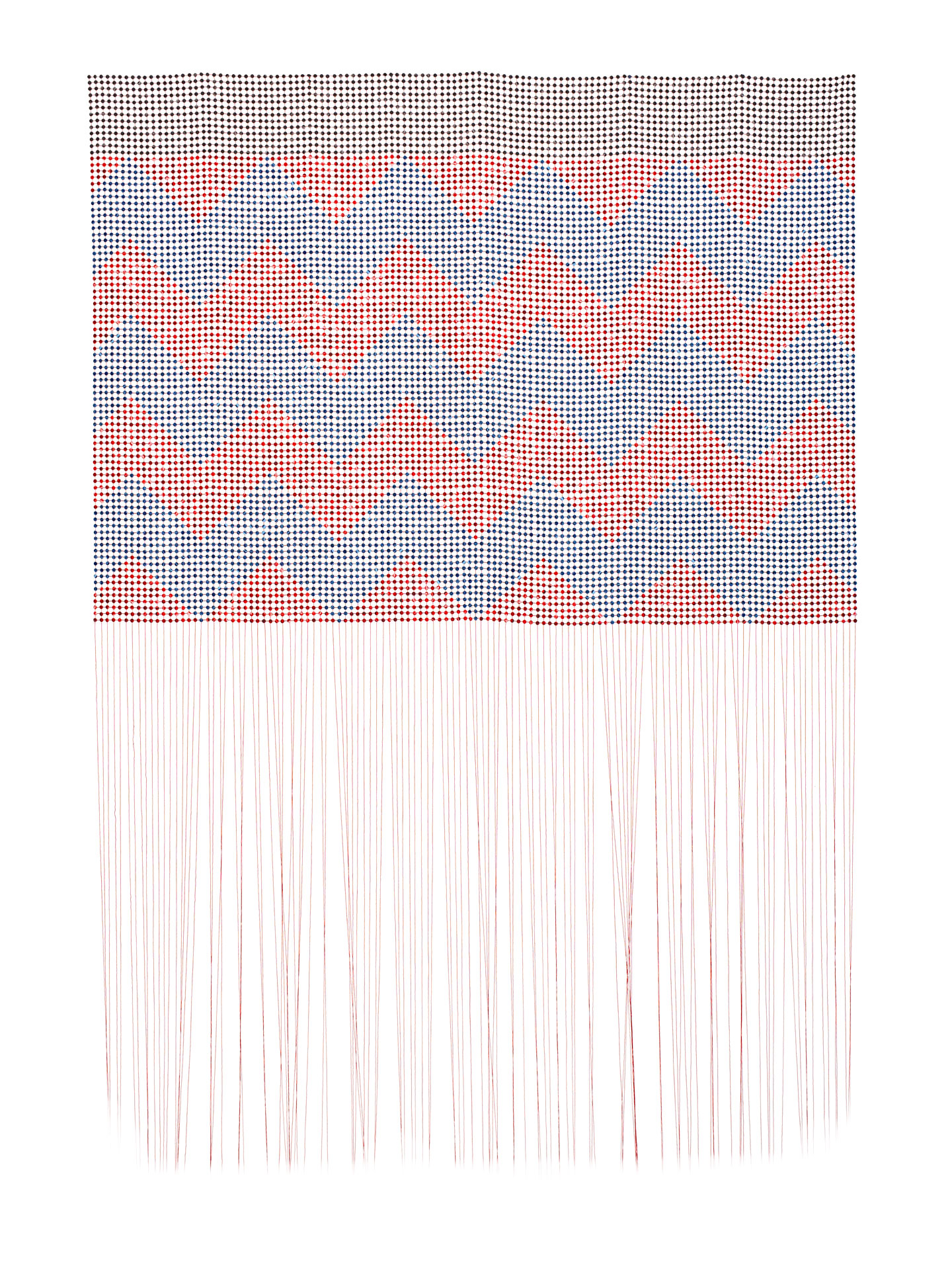

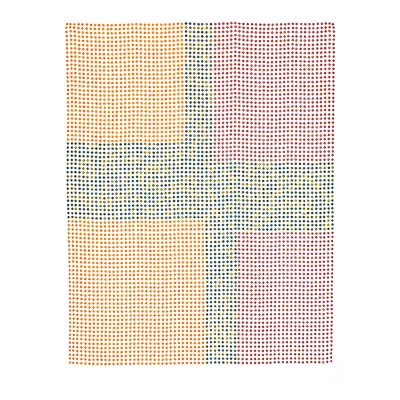

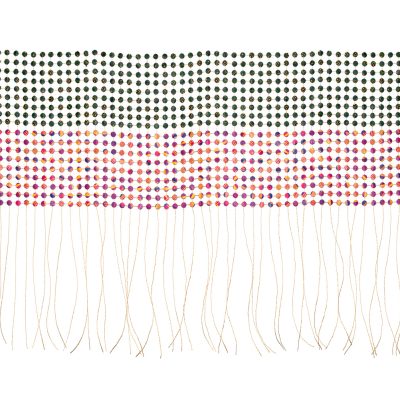

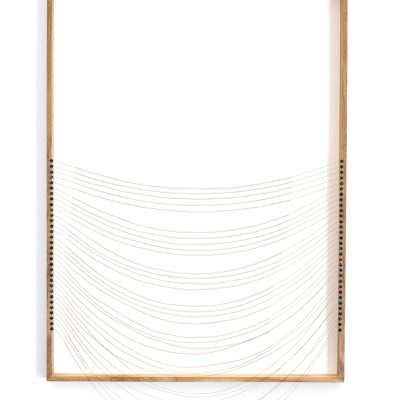

Trained as a printmaker, a discipline that demands precision, Kavula approaches her process with reverence, “I wouldn’t take shortcuts.” For this reason, Kavula’s process begins with a set formula: preparing the grids of thread with calculated precision. A step she describes as needing to be “extremely perfect,” this foundation acts as her canvas. Once established, wood glue is used to place the discs she punched at the points where the threads meet. Commentary on the series of intersections, connections and disconnections that make what people see when they encounter each other. Although presenting one image at a distance, upon closer inspection exists an opportunity for in-depth engagement.

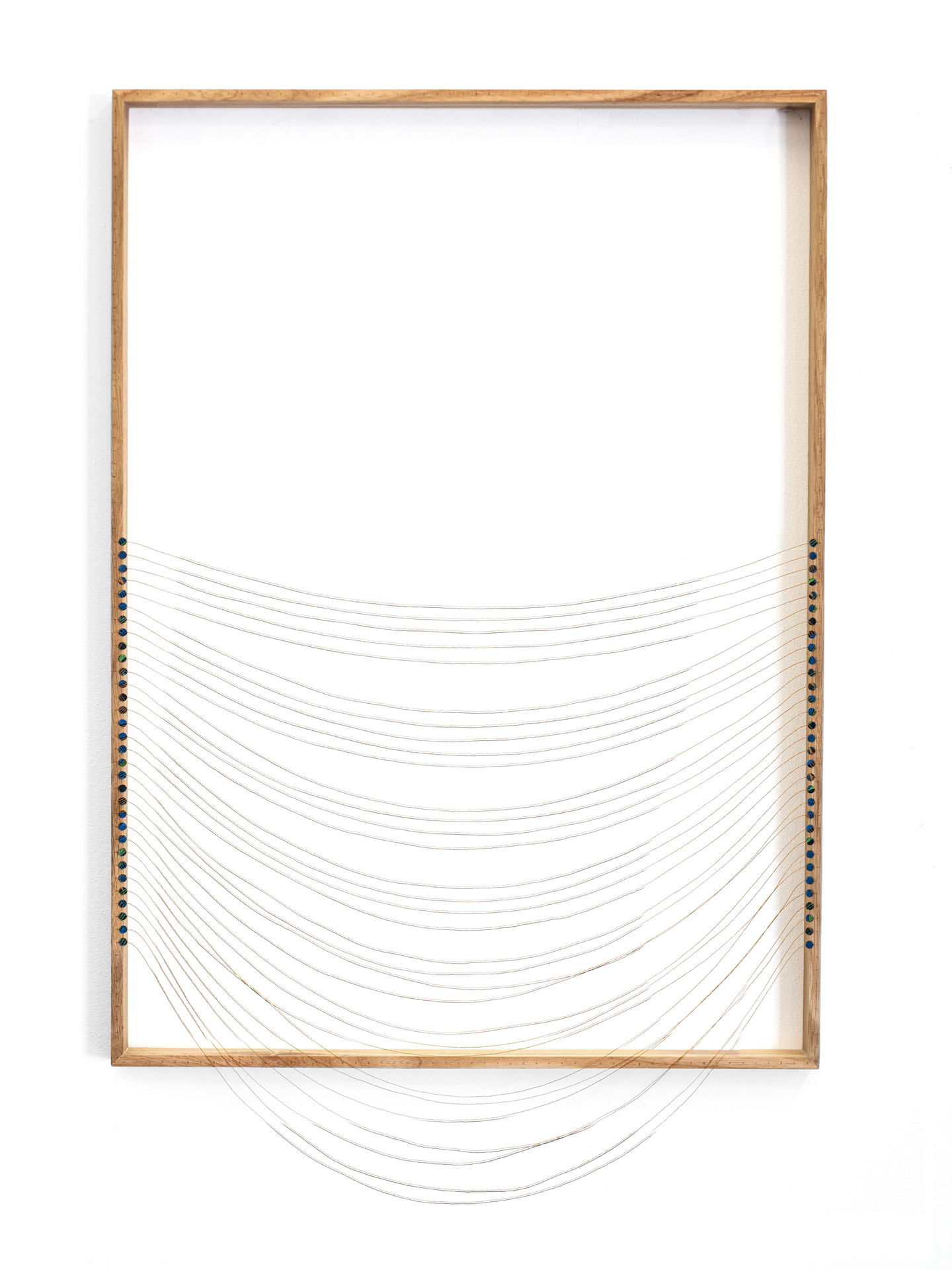

Still attached to a wooden frame, Tshenolo (2022) uses bareness and the audiencies ability to see right through the work to illustrate a range of emotions related to attachment, ranging from vulnerability to transparency. Then, with the punched discs coming to an abrupt end, leaving the usually graded threads to become tassels, I lost you (2022) materialises both abandonment and how unraveled grief.

Working with upholstery thread, wood glue and seshweshwe fabric, the materiality in Kavula’s work acknowledges the domestic without being tied down to it. So although charged with resonance, in resisting prompts to prescribe meaning to her work, Kavula’s work becomes an open forum. An invitation to project and personalise, the potential readings are subject to the audience.

Okay with how exhibitions attract a blend of aesthetic apathetic viewers and probing spectators, Kavula’s only desired outcome is for the audience to at least study and acknowledge the work’s intricacies. “There is an element of needing to be present no matter what is going on,” she says, suggesting that the work demands a mindful stillness. Giving in and closely inspecting the delicate, miniscule and tedious labour that goes into her soft but grand works, Kavula’s Lewatle displays the artist’s commitment to maintaining a thorough studio practice.

In spite of asserting titles to the works and overall exhibition, giving in and closely inspecting the delicate, miniscule and tedious labour that goes into her soft but grand works only reinforces Jabulile Dlamini-Qwesha’s words for Kavula’s prior solo exhibition: “Bonolo Kavula shows you what you’re prepared to see”

Subscribe

Subscribe

For exclusive news, tickets and invites delivered every week