In A Protea Is Not a Flower, curator Khanyisile Mawhayi presents a thoughtful meditation on exile, nationhood, and creative inheritance. The exhibition brings together historical figures such as Gerard Sekoto, Bessie Head, and Don Mattera with contemporary artists Lerato Shadi and Robin Rhode, tracing the complex terrains of displacement and voluntary exile across time and geography.

The exhibition’s title, drawn from Mattera’s 1983 poem, sets an intellectual tone. The protea, South Africa’s national emblem, is reframed as a site of contradiction, endurance, and reflection rather than straightforward pride. “I think to claim that the protea is not a flower,” Mawhayi explains, “is to say that these things we pride ourselves on, that define nationhood, and that make us feel part of something, operate at a deeper level. It’s not just a flower. It carries the weight of many other things.”

Mawhayi uses this inversion to explore the deeper tensions in South African identity, questioning what it means to inherit a nation shaped by both internal and external exile. This conceptual framing is compelling, giving the exhibition focus and clarity that might otherwise be lost in its breadth.

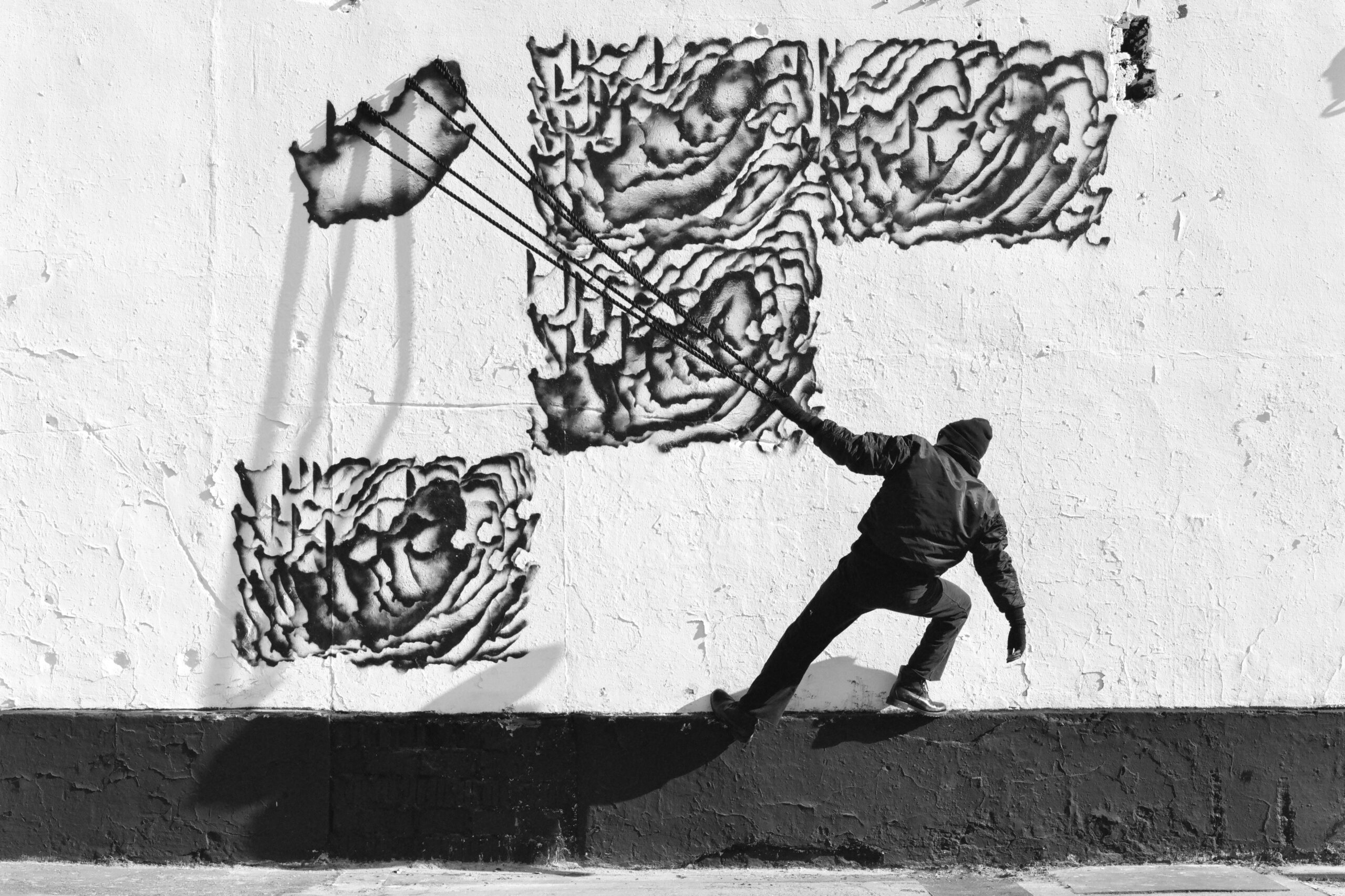

The curatorial strategy, which pairs archival material with contemporary interventions, often succeeds in generating meaningful dialogue across generations. Sekoto’s Le Massacre de Sharpeville engages with Shadi’s Maropeng, while Rhode’s Twilight echoes gestures of resistance first articulated in Mattera’s poetry. “We wanted to ask,” Mawhayi reflects, “what is the difference between someone who is an immigrant and someone in voluntary exile? Because voluntary exile sounds like an oxymoron. How can you volunteer to be in exile?”

These connections feel deliberate, though occasionally they risk seeming slightly constructed rather than organically emerging. Nevertheless, the exhibition’s insistence on thinking about exile as a condition of creativity is both persuasive and intellectually stimulating. As Mawhayi notes, “Exile can be physical, intellectual, or psychological. What it does, whether through absence or displacement, is shape creative output. It makes artists rethink what home means and what belonging means.”

The archival research underpinning the show is meticulous. Sekoto’s personal letters and sketches, alongside Head’s correspondence, offer intimate glimpses into lives shaped by displacement, while Mawhayi’s curatorial choices emphasize emotional resonance alongside historical context. “With Bessie Head,” she recalls, “we went to Botswana and read her letters. She wrote to everyone, from Toni Morrison to Robert Sobukwe. And with Sekoto, we discovered his entire archive, including his suitcase, letters, songs, and sketches at Iziko. It’s their best-kept secret.”

Some sections of the exhibition, however, lean heavily on documentation, and moments of visual or performative impact could have been stronger to balance the textual density.

Where the exhibition truly excels is in its refusal to sentimentalize exile. Mawhayi presents displacement not merely as loss but as a condition that fosters reflection, imagination, and connection. “Don Mattera, Bessie Head, Gerard Sekoto—they each experienced exile differently,” she observes. “For Don, it was an internal exile. He couldn’t speak publicly or write under his own name for ten years. Yet all of them found ways to keep creating. That is what fascinates me: how exile becomes generative.”

The protea is a fitting emblem. It survives under unexpected conditions, adapting to its environment while retaining its integrity. In this sense, the exhibition succeeds not only as a historical survey but also as a meditation on navigating the world while remaining tethered to home, memory, and identity. Mawhayi quotes Robert Sobukwe, who once wrote to Bessie Head that he could never be a refugee on the African continent because the continent belongs to its people. “That is what I want visitors to take away,” she says. “We belong to the continent, and the continent belongs to us.”Overall, A Protea Is Not a Flower is a thoughtful, rigorous exhibition that asks challenging questions without offering easy answers. It occasionally wavers under its own ambition, but the stakes it sets for thinking about exile, nationhood, and creative practice make it a significant and timely contribution to contemporary South African art.