Curated by Georgia Nasseh and Gillian Fleischmann, Glimpses of the Now is an invitation to look at life as an event that unfolds like a visual palimpsest. It is layered, torn, rearranged. Anchored by Sam Nhlengethwa’s 2003 lithographic collage series Glimpses of the 50s and 60s, the exhibition moves across time and geographies. Pairing historic meditation on Black life under apartheid with contemporary voices from Brazil, Cameroon, Lesotho and South Africa, the result is not reading collage as a style. Instead, here collage is presented as a method; a way to rupture the authority of the image and reconfigure the politics of looking.

When prodded on the premise that led to this stream of research, Nasseh recalls the question she asked herself: “Why does collage keep coming up?”. A research fellow in the literature of the Global South at King’s College, Nasseh explores multilingualism as it plays out in literature. Her fascination with the form did not begin in the visual arts but in literature and decolonial linguistics. “Language too is a collage. In the Global South, our languages are not pure or linear. Portuguese in Brazil, for instance, is shaped by Amerindian and African tongues. There is no singular origin,” she explains. It is hybridity as a living condition.

This idea of collage as a decolonial gesture threads through the exhibition. Glimpses of the Now features six contemporary artists: Alexia Ferreira, Ethel Tawe, Gê Viana, Neo Matloga, Phumulani Ntuli and Thato Toeba. Each artist approaches the fragment not only as a visual tool but as a conceptual one. Through the fragment they explore migration, memory, postcolonial desire and the limits of the archive.

Here, collage is not about aesthetic pleasure. Unlike its spoken and written counterpart, visual collage is not afforded seamlessness. It is about rupture and refusal. “When you collage,” adds Fleischmann, “you collapse the rules. There are rules when sourcing and referencing; things that need to be considered when sourcing from an archive. But collage lets you break them.” A part of the curatorial team at Javett-UP, Fleischmann is an artist and cultural producer interested in exhibition, film and publication making. Together with Nasseh, Fleischmann came together through the BRIDGE Fellowship between the Javett-UP Art Centre and The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH) at the University of Oxford. Developed in 2022, the fellowship looks to build bridges that will facilitate intercontinental, multidisciplinary, practice expanding crosspollination.

She spoke of her collaboration with Nasseh as one built on instinct and urgency. “Georgia had this observation about Brazil, how inking and collage were so present there. And I thought, it’s the same here. That recognition, the same impulse from two sides of the South, that was our spark.”

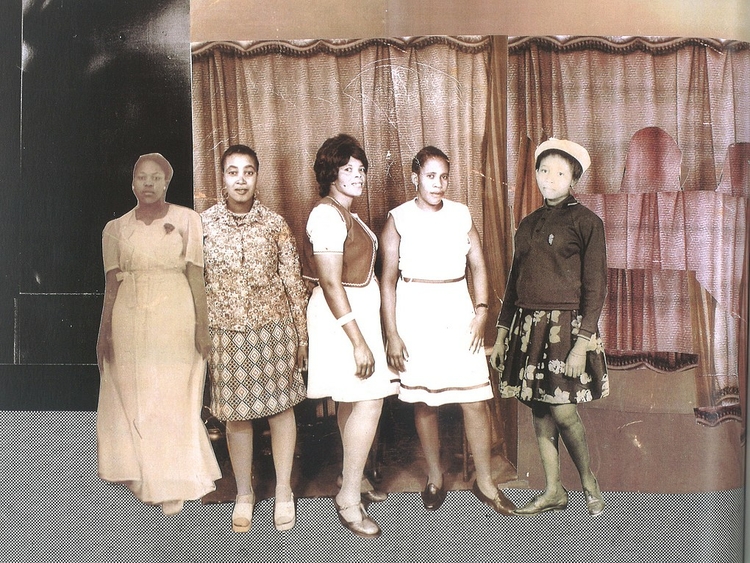

A catalyst to the exhibition, Nhlengethwa’s Glimpses of the 50s and 60s struck a chord for Nasseh before she had even arrived in Johannesburg. “I come from Rio, a city marked by favelas, our own form of townships. When I saw Sam Nhlengethwa’s depictions of township life, the improvisation, the density, the textures, I felt like I was looking at home. Those urban assemblages are collages too.”

The resonance between Rio and Johannesburg is more than visual. It is historical. “This year in Brazil marks 40 years of democracy,” Nasseh noted. “South Africa, 30. So when we ran collage workshops with students from UP and Oxford, we worked with materials from both our national archives. We asked how our transitions out of dictatorship speak to one another. How collage can help us read the overlapping truths of those journeys.”

It is in the way Gê Viana collages, animates and re-signifies representations black Brazilians, recasting Jean-Baptiste Debret’s depictions as agents of joy. Similarly, South African artist Neo Matloga offers scenes of familial intimacy. These scenes acknowledge historical violence without being held captive by it. “There’s one work we included that takes place on a beach,” Nasseh explained. “In Rio, beaches are supposed to be democratic spaces. But access is manipulated. Bus lines are changed. People are kept out. That’s segregation. So when I saw Matloga’s image, it hit hard. It showed how apartheid and Brazilian inequality can mirror each other in the most mundane places.”

Glimpses of the Now is not only an exhibition. It is the culmination of something research-led but publicly meaningful. For Nasseh, the experience has reframed what it means to be a scholar. “In academia, you write papers that maybe two people read,” she said. “But in Johannesburg, people do walkabouts, open studios, and street conversations. Being here made me want to do it. Working with Gillian reminded me how rare and beautiful real collaboration can be.”

In the end, Glimpses of the Now holds a quiet but radical proposition. That collage is not only a medium, but a way of being in a fractured world. A way to hold contradiction without resolving it. A way of seeing the now not as a single image, but as a constellation of fragments. Gathered, recomposed and still in motion.